Buried somewhere near the beginning of this site’s existence, there’s a piece on the film

Rushmore wherein I went back and re-read The Catcher in the Rye for the first time in a

decade-plus. The movie reminded me of the book; more specifically, Max Fischer reminded

me of Holden Caulfield. I don’t know--thinking about that now, the connection seems a

little tenuous beyond the prep-school angle.

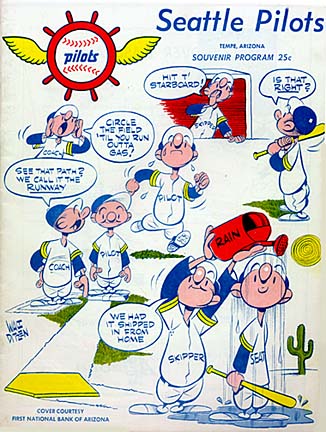

I’ve just finished rereading Jim Bouton’s Ball Four for something I’ve been working on, a

rereading that in this case spans at least 25 years. I remember getting Dave MacIntosh to

read it during the Nerve days, and also Scott Woods, although Scott tells me now that he’d

already read it at that point. I probably read it again myself around that time. That would

have been the mid-‘80s, so let’s say 25 years. Jim Bouton turned 75 this year. He’s older

now than Casey Stengel was when he managed the Mets.

Unlike my revisitation of A Catcher in the Rye 15 years ago, Ball Four held up just fine

this time around. Much better than that, actually--I’ve never felt surer about naming it

as one of the key influences on my writing, on me as a baseball fan, and on my general

outlook on life. Yes, I have a general outlook on life. I’m not sure if mine is any more

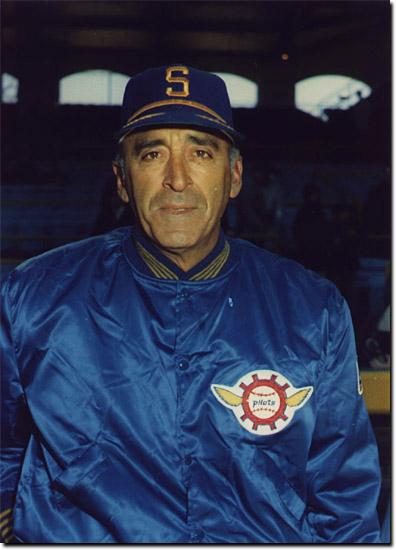

philosophical than the one espoused by Joe Schultz in Ball Four--“Well, boys, it's a round

ball and a round bat and you got to hit the ball square”--but I bow down to Joe in the

philosophy department, so no shame there.

When I first read Ball Four in high school, the thing I most gravitated towards was its

jaundiced view of the player-coach dynamic. Bouton’s two managers in the book--Schultz

in Seattle, and then Harry Walker after he’s traded to Houston--mostly got a pass, but

the inane proclamations and less-than-forthright maneuvering of some of the other

coaches, particularly Sal Maglie, had special resonance for me at a time when I lived

out my own version of Ball Four as the mop-guy on my high-school basketball team. I

loved the humour, loved Schultz (a character beyond the powers of literary invention),

and pretty much loved anything having to do with baseball in those days, but it was the

book’s confirmation of my growing sense that the people running the show were clueless

that meant the most to me then.

That part is still there, of course, and it still makes me laugh. Eddie O’Brien (“Mr.

Small Stuff”) checking up on every last pointless detail, Maglie second-guessing so often

that Bouton has to invent the concept of the first-guess second-guess, Sibby Sisti put-

tering around on his little cart for no discernible reason beyond qualifying for a pen-

sion--Ball Four remains my Catch-22, Dr. Strangelove, and Mad magazine all rolled into

one, the book that more than anything else hyper-sensitized me to the clear and present

absurdity all around. (Sisti does get off what is possibly my favorite line in the book,

after the Pilots’ first and last annual father-kid game: “Forty runs, for crissakes, and

nobody gets knocked down.”) But it was a couple of other things that jumped out at me

even more this time. The fact that I’m a coach myself now, and a teacher who nags my

students about every last pointless detail, I’m sure none of that has any connection

to my evolving viewpoint.

The first was how incredibly good Bouton is on the major issues of the day, primarily

race and the war. Ball Four was written squarely in the middle of a famously chaotic

moment, the events of which should be familiar, and far from dodging what was playing

out in the rest of the country, Bouton tries to make sense of things. He closely observes

the interactions between white and black players on both the Pilots and the Astros, no-

ticing key differences between the two clubs. He ridicules the idea that Houston would

be asking for trouble if they traded for Dick (“Richie,” as he was called against his

wishes then) Allen down the stretch: “Humph. I wonder what the Astros would give to have

him come to bat just fifteen times for us this season.” And he’s open about his own fal-

libility, admitting that his views on integrated marriage--remember, this is a notori-

ously conservative sport almost 50 years ago--have been upended. With regards to Viet

Nam, he’s completely on the side of those protesting the war. So much so that he (along

with kindred spirits Steve Hovley and Mike Marshall) senses reluctance among the other

players to engage him on the subject. Which is not always a bad thing--in the case of

hardline farm guy Gene Brabender, Bouton describes him as someone who looks like he’d

“crush your spleen” if you got under his skin.

Coming full circle from the high-school me, the other thing that really came through

this time was how much of an unabashed fan Bouton is. I think I always picked up on that

sentiment, but never so clearly. There’s a love and a reverence for the game all through

Ball Four, often for those very same absurdities that otherwise exasperate Bouton. You

see this especially in his back-and-forth with Brabender and Fred Talbot, or Wade Blasin-

game over on the Astros, guys he has zero in common with beyond the game itself. But

they’re all able to make him laugh--they’re all bonded by the somewhat surreal nature

of what they do for a living, bonded by their derision for the coaches and owners, and

bonded by the same insecurities that were a given with guys who existed at the margins

in the years before free agency. (The emergence of Marvin Miller and the player’s growing

labor awareness is one of the book’s most vital subplots, as is Bouton’s ongoing strug-

gle to master a schizophrenic pitch, the knuckleball.)

There’s a heavily-trafficked website called Baseball-Reference where you can sponsor a

player’s stat page. You pay them a set amount, you get your name on the page as the spon-

sor, and you get to write a line or two about the player. If you want to sponsor Willie

Mays or Ted Williams, forget it, unless you’re willing to pay a few hundred dollars a year.

(Mays and Koufax are both available at the moment, somewhat surprisingly; Mays goes for

$455, Koufax for $305.) But you can also sponsor pages for as little as $10 a year, and yes,

the Seattle Pilots were just waiting there for me, alone and unloved and unsponsored. Right

now, I’ve got three Pilots: Merritt Ranew, Talbot, and--quite possibly my proudest pos-

session in the world--Joe Schultz. I plan to sponsor a few more, I’ve just been lazy about

following through. Bouton himself, unfortunately, looks to be out of reach--the “Law Offices

of Jeffrey Lichtman” have had the page for a number of years now (probably out of my price

range anyway).

The sponsorships are just one of many ways in which Ball Four has stayed with me through the

years. More than a great baseball writer, Bouton--like Bill James, like Robert Creamer, like

Joe Posnanski--is simply a great writer. I can’t think of a better illustration of that than

the book’s famous closing sentence:

“You see, you spend a good piece of your life gripping a baseball, and in the end it turns

out that it was the other way around all the time.”

Honestly, that’s as good as The Great Gatsby’s closing sentence.

Buried somewhere near the beginning of this site’s existence, there’s a piece on the film

Rushmore wherein I went back and re-read The Catcher in the Rye for the first time in a

decade-plus. The movie reminded me of the book; more specifically, Max Fischer reminded

me of Holden Caulfield. I don’t know--thinking about that now, the connection seems a

little tenuous beyond the prep-school angle.

I’ve just finished rereading Jim Bouton’s Ball Four for something I’ve been working on, a

rereading that in this case spans at least 25 years. I remember getting Dave MacIntosh to

read it during the Nerve days, and also Scott Woods, although Scott tells me now that he’d

already read it at that point. I probably read it again myself around that time. That would

have been the mid-‘80s, so let’s say 25 years. Jim Bouton turned 75 this year. He’s older

now than Casey Stengel was when he managed the Mets.

Unlike my revisitation of A Catcher in the Rye 15 years ago, Ball Four held up just fine

this time around. Much better than that, actually--I’ve never felt surer about naming it

as one of the key influences on my writing, on me as a baseball fan, and on my general

outlook on life. Yes, I have a general outlook on life. I’m not sure if mine is any more

philosophical than the one espoused by Joe Schultz in Ball Four--“Well, boys, it's a round

ball and a round bat and you got to hit the ball square”--but I bow down to Joe in the

philosophy department, so no shame there.

When I first read Ball Four in high school, the thing I most gravitated towards was its

jaundiced view of the player-coach dynamic. Bouton’s two managers in the book--Schultz

in Seattle, and then Harry Walker after he’s traded to Houston--mostly got a pass, but

the inane proclamations and less-than-forthright maneuvering of some of the other

coaches, particularly Sal Maglie, had special resonance for me at a time when I lived

out my own version of Ball Four as the mop-guy on my high-school basketball team. I

loved the humour, loved Schultz (a character beyond the powers of literary invention),

and pretty much loved anything having to do with baseball in those days, but it was the

book’s confirmation of my growing sense that the people running the show were clueless

that meant the most to me then.

That part is still there, of course, and it still makes me laugh. Eddie O’Brien (“Mr.

Small Stuff”) checking up on every last pointless detail, Maglie second-guessing so often

that Bouton has to invent the concept of the first-guess second-guess, Sibby Sisti put-

tering around on his little cart for no discernible reason beyond qualifying for a pen-

sion--Ball Four remains my Catch-22, Dr. Strangelove, and Mad magazine all rolled into

one, the book that more than anything else hyper-sensitized me to the clear and present

absurdity all around. (Sisti does get off what is possibly my favorite line in the book,

after the Pilots’ first and last annual father-kid game: “Forty runs, for crissakes, and

nobody gets knocked down.”) But it was a couple of other things that jumped out at me

even more this time. The fact that I’m a coach myself now, and a teacher who nags my

students about every last pointless detail, I’m sure none of that has any connection

to my evolving viewpoint.

The first was how incredibly good Bouton is on the major issues of the day, primarily

race and the war. Ball Four was written squarely in the middle of a famously chaotic

moment, the events of which should be familiar, and far from dodging what was playing

out in the rest of the country, Bouton tries to make sense of things. He closely observes

the interactions between white and black players on both the Pilots and the Astros, no-

ticing key differences between the two clubs. He ridicules the idea that Houston would

be asking for trouble if they traded for Dick (“Richie,” as he was called against his

wishes then) Allen down the stretch: “Humph. I wonder what the Astros would give to have

him come to bat just fifteen times for us this season.” And he’s open about his own fal-

libility, admitting that his views on integrated marriage--remember, this is a notori-

ously conservative sport almost 50 years ago--have been upended. With regards to Viet

Nam, he’s completely on the side of those protesting the war. So much so that he (along

with kindred spirits Steve Hovley and Mike Marshall) senses reluctance among the other

players to engage him on the subject. Which is not always a bad thing--in the case of

hardline farm guy Gene Brabender, Bouton describes him as someone who looks like he’d

“crush your spleen” if you got under his skin.

Coming full circle from the high-school me, the other thing that really came through

this time was how much of an unabashed fan Bouton is. I think I always picked up on that

sentiment, but never so clearly. There’s a love and a reverence for the game all through

Ball Four, often for those very same absurdities that otherwise exasperate Bouton. You

see this especially in his back-and-forth with Brabender and Fred Talbot, or Wade Blasin-

game over on the Astros, guys he has zero in common with beyond the game itself. But

they’re all able to make him laugh--they’re all bonded by the somewhat surreal nature

of what they do for a living, bonded by their derision for the coaches and owners, and

bonded by the same insecurities that were a given with guys who existed at the margins

in the years before free agency. (The emergence of Marvin Miller and the player’s growing

labor awareness is one of the book’s most vital subplots, as is Bouton’s ongoing strug-

gle to master a schizophrenic pitch, the knuckleball.)

There’s a heavily-trafficked website called Baseball-Reference where you can sponsor a

player’s stat page. You pay them a set amount, you get your name on the page as the spon-

sor, and you get to write a line or two about the player. If you want to sponsor Willie

Mays or Ted Williams, forget it, unless you’re willing to pay a few hundred dollars a year.

(Mays and Koufax are both available at the moment, somewhat surprisingly; Mays goes for

$455, Koufax for $305.) But you can also sponsor pages for as little as $10 a year, and yes,

the Seattle Pilots were just waiting there for me, alone and unloved and unsponsored. Right

now, I’ve got three Pilots: Merritt Ranew, Talbot, and--quite possibly my proudest pos-

session in the world--Joe Schultz. I plan to sponsor a few more, I’ve just been lazy about

following through. Bouton himself, unfortunately, looks to be out of reach--the “Law Offices

of Jeffrey Lichtman” have had the page for a number of years now (probably out of my price

range anyway).

The sponsorships are just one of many ways in which Ball Four has stayed with me through the

years. More than a great baseball writer, Bouton--like Bill James, like Robert Creamer, like

Joe Posnanski--is simply a great writer. I can’t think of a better illustration of that than

the book’s famous closing sentence:

“You see, you spend a good piece of your life gripping a baseball, and in the end it turns

out that it was the other way around all the time.”

Honestly, that’s as good as The Great Gatsby’s closing sentence.

Buried somewhere near the beginning of this site’s existence, there’s a piece on the film

Rushmore wherein I went back and re-read The Catcher in the Rye for the first time in a

decade-plus. The movie reminded me of the book; more specifically, Max Fischer reminded

me of Holden Caulfield. I don’t know--thinking about that now, the connection seems a

little tenuous beyond the prep-school angle.

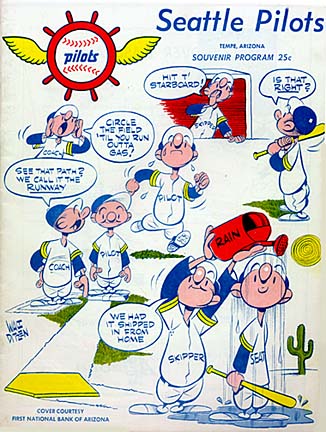

I’ve just finished rereading Jim Bouton’s Ball Four for something I’ve been working on, a

rereading that in this case spans at least 25 years. I remember getting Dave MacIntosh to

read it during the Nerve days, and also Scott Woods, although Scott tells me now that he’d

already read it at that point. I probably read it again myself around that time. That would

have been the mid-‘80s, so let’s say 25 years. Jim Bouton turned 75 this year. He’s older

now than Casey Stengel was when he managed the Mets.

Unlike my revisitation of A Catcher in the Rye 15 years ago, Ball Four held up just fine

this time around. Much better than that, actually--I’ve never felt surer about naming it

as one of the key influences on my writing, on me as a baseball fan, and on my general

outlook on life. Yes, I have a general outlook on life. I’m not sure if mine is any more

philosophical than the one espoused by Joe Schultz in Ball Four--“Well, boys, it's a round

ball and a round bat and you got to hit the ball square”--but I bow down to Joe in the

philosophy department, so no shame there.

When I first read Ball Four in high school, the thing I most gravitated towards was its

jaundiced view of the player-coach dynamic. Bouton’s two managers in the book--Schultz

in Seattle, and then Harry Walker after he’s traded to Houston--mostly got a pass, but

the inane proclamations and less-than-forthright maneuvering of some of the other

coaches, particularly Sal Maglie, had special resonance for me at a time when I lived

out my own version of Ball Four as the mop-guy on my high-school basketball team. I

loved the humour, loved Schultz (a character beyond the powers of literary invention),

and pretty much loved anything having to do with baseball in those days, but it was the

book’s confirmation of my growing sense that the people running the show were clueless

that meant the most to me then.

That part is still there, of course, and it still makes me laugh. Eddie O’Brien (“Mr.

Small Stuff”) checking up on every last pointless detail, Maglie second-guessing so often

that Bouton has to invent the concept of the first-guess second-guess, Sibby Sisti put-

tering around on his little cart for no discernible reason beyond qualifying for a pen-

sion--Ball Four remains my Catch-22, Dr. Strangelove, and Mad magazine all rolled into

one, the book that more than anything else hyper-sensitized me to the clear and present

absurdity all around. (Sisti does get off what is possibly my favorite line in the book,

after the Pilots’ first and last annual father-kid game: “Forty runs, for crissakes, and

nobody gets knocked down.”) But it was a couple of other things that jumped out at me

even more this time. The fact that I’m a coach myself now, and a teacher who nags my

students about every last pointless detail, I’m sure none of that has any connection

to my evolving viewpoint.

The first was how incredibly good Bouton is on the major issues of the day, primarily

race and the war. Ball Four was written squarely in the middle of a famously chaotic

moment, the events of which should be familiar, and far from dodging what was playing

out in the rest of the country, Bouton tries to make sense of things. He closely observes

the interactions between white and black players on both the Pilots and the Astros, no-

ticing key differences between the two clubs. He ridicules the idea that Houston would

be asking for trouble if they traded for Dick (“Richie,” as he was called against his

wishes then) Allen down the stretch: “Humph. I wonder what the Astros would give to have

him come to bat just fifteen times for us this season.” And he’s open about his own fal-

libility, admitting that his views on integrated marriage--remember, this is a notori-

ously conservative sport almost 50 years ago--have been upended. With regards to Viet

Nam, he’s completely on the side of those protesting the war. So much so that he (along

with kindred spirits Steve Hovley and Mike Marshall) senses reluctance among the other

players to engage him on the subject. Which is not always a bad thing--in the case of

hardline farm guy Gene Brabender, Bouton describes him as someone who looks like he’d

“crush your spleen” if you got under his skin.

Coming full circle from the high-school me, the other thing that really came through

this time was how much of an unabashed fan Bouton is. I think I always picked up on that

sentiment, but never so clearly. There’s a love and a reverence for the game all through

Ball Four, often for those very same absurdities that otherwise exasperate Bouton. You

see this especially in his back-and-forth with Brabender and Fred Talbot, or Wade Blasin-

game over on the Astros, guys he has zero in common with beyond the game itself. But

they’re all able to make him laugh--they’re all bonded by the somewhat surreal nature

of what they do for a living, bonded by their derision for the coaches and owners, and

bonded by the same insecurities that were a given with guys who existed at the margins

in the years before free agency. (The emergence of Marvin Miller and the player’s growing

labor awareness is one of the book’s most vital subplots, as is Bouton’s ongoing strug-

gle to master a schizophrenic pitch, the knuckleball.)

There’s a heavily-trafficked website called Baseball-Reference where you can sponsor a

player’s stat page. You pay them a set amount, you get your name on the page as the spon-

sor, and you get to write a line or two about the player. If you want to sponsor Willie

Mays or Ted Williams, forget it, unless you’re willing to pay a few hundred dollars a year.

(Mays and Koufax are both available at the moment, somewhat surprisingly; Mays goes for

$455, Koufax for $305.) But you can also sponsor pages for as little as $10 a year, and yes,

the Seattle Pilots were just waiting there for me, alone and unloved and unsponsored. Right

now, I’ve got three Pilots: Merritt Ranew, Talbot, and--quite possibly my proudest pos-

session in the world--Joe Schultz. I plan to sponsor a few more, I’ve just been lazy about

following through. Bouton himself, unfortunately, looks to be out of reach--the “Law Offices

of Jeffrey Lichtman” have had the page for a number of years now (probably out of my price

range anyway).

The sponsorships are just one of many ways in which Ball Four has stayed with me through the

years. More than a great baseball writer, Bouton--like Bill James, like Robert Creamer, like

Joe Posnanski--is simply a great writer. I can’t think of a better illustration of that than

the book’s famous closing sentence:

“You see, you spend a good piece of your life gripping a baseball, and in the end it turns

out that it was the other way around all the time.”

Honestly, that’s as good as The Great Gatsby’s closing sentence.

Buried somewhere near the beginning of this site’s existence, there’s a piece on the film

Rushmore wherein I went back and re-read The Catcher in the Rye for the first time in a

decade-plus. The movie reminded me of the book; more specifically, Max Fischer reminded

me of Holden Caulfield. I don’t know--thinking about that now, the connection seems a

little tenuous beyond the prep-school angle.

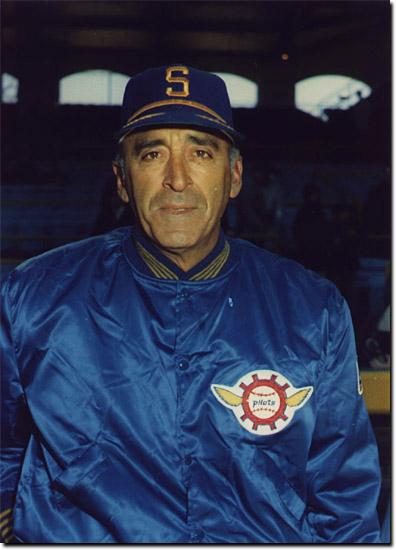

I’ve just finished rereading Jim Bouton’s Ball Four for something I’ve been working on, a

rereading that in this case spans at least 25 years. I remember getting Dave MacIntosh to

read it during the Nerve days, and also Scott Woods, although Scott tells me now that he’d

already read it at that point. I probably read it again myself around that time. That would

have been the mid-‘80s, so let’s say 25 years. Jim Bouton turned 75 this year. He’s older

now than Casey Stengel was when he managed the Mets.

Unlike my revisitation of A Catcher in the Rye 15 years ago, Ball Four held up just fine

this time around. Much better than that, actually--I’ve never felt surer about naming it

as one of the key influences on my writing, on me as a baseball fan, and on my general

outlook on life. Yes, I have a general outlook on life. I’m not sure if mine is any more

philosophical than the one espoused by Joe Schultz in Ball Four--“Well, boys, it's a round

ball and a round bat and you got to hit the ball square”--but I bow down to Joe in the

philosophy department, so no shame there.

When I first read Ball Four in high school, the thing I most gravitated towards was its

jaundiced view of the player-coach dynamic. Bouton’s two managers in the book--Schultz

in Seattle, and then Harry Walker after he’s traded to Houston--mostly got a pass, but

the inane proclamations and less-than-forthright maneuvering of some of the other

coaches, particularly Sal Maglie, had special resonance for me at a time when I lived

out my own version of Ball Four as the mop-guy on my high-school basketball team. I

loved the humour, loved Schultz (a character beyond the powers of literary invention),

and pretty much loved anything having to do with baseball in those days, but it was the

book’s confirmation of my growing sense that the people running the show were clueless

that meant the most to me then.

That part is still there, of course, and it still makes me laugh. Eddie O’Brien (“Mr.

Small Stuff”) checking up on every last pointless detail, Maglie second-guessing so often

that Bouton has to invent the concept of the first-guess second-guess, Sibby Sisti put-

tering around on his little cart for no discernible reason beyond qualifying for a pen-

sion--Ball Four remains my Catch-22, Dr. Strangelove, and Mad magazine all rolled into

one, the book that more than anything else hyper-sensitized me to the clear and present

absurdity all around. (Sisti does get off what is possibly my favorite line in the book,

after the Pilots’ first and last annual father-kid game: “Forty runs, for crissakes, and

nobody gets knocked down.”) But it was a couple of other things that jumped out at me

even more this time. The fact that I’m a coach myself now, and a teacher who nags my

students about every last pointless detail, I’m sure none of that has any connection

to my evolving viewpoint.

The first was how incredibly good Bouton is on the major issues of the day, primarily

race and the war. Ball Four was written squarely in the middle of a famously chaotic

moment, the events of which should be familiar, and far from dodging what was playing

out in the rest of the country, Bouton tries to make sense of things. He closely observes

the interactions between white and black players on both the Pilots and the Astros, no-

ticing key differences between the two clubs. He ridicules the idea that Houston would

be asking for trouble if they traded for Dick (“Richie,” as he was called against his

wishes then) Allen down the stretch: “Humph. I wonder what the Astros would give to have

him come to bat just fifteen times for us this season.” And he’s open about his own fal-

libility, admitting that his views on integrated marriage--remember, this is a notori-

ously conservative sport almost 50 years ago--have been upended. With regards to Viet

Nam, he’s completely on the side of those protesting the war. So much so that he (along

with kindred spirits Steve Hovley and Mike Marshall) senses reluctance among the other

players to engage him on the subject. Which is not always a bad thing--in the case of

hardline farm guy Gene Brabender, Bouton describes him as someone who looks like he’d

“crush your spleen” if you got under his skin.

Coming full circle from the high-school me, the other thing that really came through

this time was how much of an unabashed fan Bouton is. I think I always picked up on that

sentiment, but never so clearly. There’s a love and a reverence for the game all through

Ball Four, often for those very same absurdities that otherwise exasperate Bouton. You

see this especially in his back-and-forth with Brabender and Fred Talbot, or Wade Blasin-

game over on the Astros, guys he has zero in common with beyond the game itself. But

they’re all able to make him laugh--they’re all bonded by the somewhat surreal nature

of what they do for a living, bonded by their derision for the coaches and owners, and

bonded by the same insecurities that were a given with guys who existed at the margins

in the years before free agency. (The emergence of Marvin Miller and the player’s growing

labor awareness is one of the book’s most vital subplots, as is Bouton’s ongoing strug-

gle to master a schizophrenic pitch, the knuckleball.)

There’s a heavily-trafficked website called Baseball-Reference where you can sponsor a

player’s stat page. You pay them a set amount, you get your name on the page as the spon-

sor, and you get to write a line or two about the player. If you want to sponsor Willie

Mays or Ted Williams, forget it, unless you’re willing to pay a few hundred dollars a year.

(Mays and Koufax are both available at the moment, somewhat surprisingly; Mays goes for

$455, Koufax for $305.) But you can also sponsor pages for as little as $10 a year, and yes,

the Seattle Pilots were just waiting there for me, alone and unloved and unsponsored. Right

now, I’ve got three Pilots: Merritt Ranew, Talbot, and--quite possibly my proudest pos-

session in the world--Joe Schultz. I plan to sponsor a few more, I’ve just been lazy about

following through. Bouton himself, unfortunately, looks to be out of reach--the “Law Offices

of Jeffrey Lichtman” have had the page for a number of years now (probably out of my price

range anyway).

The sponsorships are just one of many ways in which Ball Four has stayed with me through the

years. More than a great baseball writer, Bouton--like Bill James, like Robert Creamer, like

Joe Posnanski--is simply a great writer. I can’t think of a better illustration of that than

the book’s famous closing sentence:

“You see, you spend a good piece of your life gripping a baseball, and in the end it turns

out that it was the other way around all the time.”

Honestly, that’s as good as The Great Gatsby’s closing sentence.